Back to GanjaTron's Site

Back to GanjaTron's Site

Sinclair ZX81 & Timex/Sinclair-1000

"Capable of running a nuclear power station!"

| Timex/Sinclair-1000 (made in Portugal with PAL video) and ZX81. Would you entrust a nuclear power station to these little doorstops? [Click to enlarge] |

My ZX81 Experience

Oh god, the ZX81... I'm ashamed to admit the ZX81 was actually the first computer I owned. Since the first computer I used was an Apple ][, I was more than spoilt and quickly ran into the ZX81's limitations. I think everyone who used a ZX81 developed a sort of love/hate relationship with it; it's a cute little black box, but it inflicted heaps of frustration on its users.

I got my ZX81 (actually a European T/S-1000) from friends who received it as a dud in the mail and awaited a replacement. I opened it up and immediately found the faulty keyboard connector, the canonical flaw of the ZX81. After snipping off the cracked foil several times I finally managed to get a connection and a working keyboard.

I didn't use the ZX81 for long, having been accustomed to more powerful systems. The tape interface never really worked for me, probably more due to the lack of a suitable tape recorder rather than a flaw in the interface itself. After about a year of suffering I finally jumped at the opportunity to get an Amstrad, and stashed the ZX81 away.

Over the years I remained jaded about the ZX81, often quoting it as the ultimate dumbed down computer. At university, I originated the absurd notion of porting UNIX to the ZX81 as the ultimate challenge. It remained an in-joke among my peers for a while, culminating in a posting I made to comp.os.linux.misc in 1996. Surprisingly, there were emailed responses.

History

Sinclair pioneered the low cost computer, and in so doing put the UK

on the map as a microcomputing nation (a tradition that was to be upheld

by Acorn and Amstrad). Sinclair introduced the ZX80 in 1980, generally

considered to be the first true low cost computer, selling for just under

£100 (or £79 as a kit). The ZX81 soon followed in 1981 as an

improved version retailing for even less. It came in a revamped case, a

lower chip count (by integrating several chips into a custom gate

The ZX series was the brainchild of the visionary Sir (!) Clive Sinclair (alias Uncle Clive). Sinclair made a name by marketing electronic gadgets such as digital watches and calculators. Sinclair's computers marked a breakthrough not only for the company, but also for the European microcomputing scene: no longer did the overpriced imports from the US dominate the market. The UK was to lead the way in European microcomputer development throughout the early to mid 80's with a number of innovative designs.

Originally sold as a kit, the ZX81 later came fully assembled to cater to a larger audience, namely beginners. Experienced users looked elsewhere. In its introduction, the Timex/Sinclair-1000 user manual makes it clear who this little computer is for, adopting a humorously condescending tone:

"We want to assure you that:

- You will enjoy computing. [Whether you like it or not]

- You will find it easy as well as enjoyable.

- You shouldn't be afraid of the computer. You are smarter than it is. So is your parakeet, for that matter. [No kidding!]

- You make mistakes as you learn. The computer will not laugh at you. [Actually, it's the other way round]

- Your mistakes will not do any harm to the computer. You can't break it by pushing the 'wrong' button. [Infact, it'll break by itself]

- You are about to take a giant step into the future. Everyone will soon be using computers in every part of their daily lives, and you will have a head start. [More like a head ache!]"

Sinclair made some bold claims regarding the possible applications of the ZX81 in their advertising, most famously the ability to run a nuclear power station! While the ZX81's limited capabilities are theoretically sufficient to employ it in a process monitoring and automation environment, its questionable reliability places the claim in the realm of absurdity. Besides, the notion of guys wearing white coats and radiation badges poking around on a ZX81 is outrageous, to say the least. It's the kind of stuff you might see in a bad Bond movie. :^)

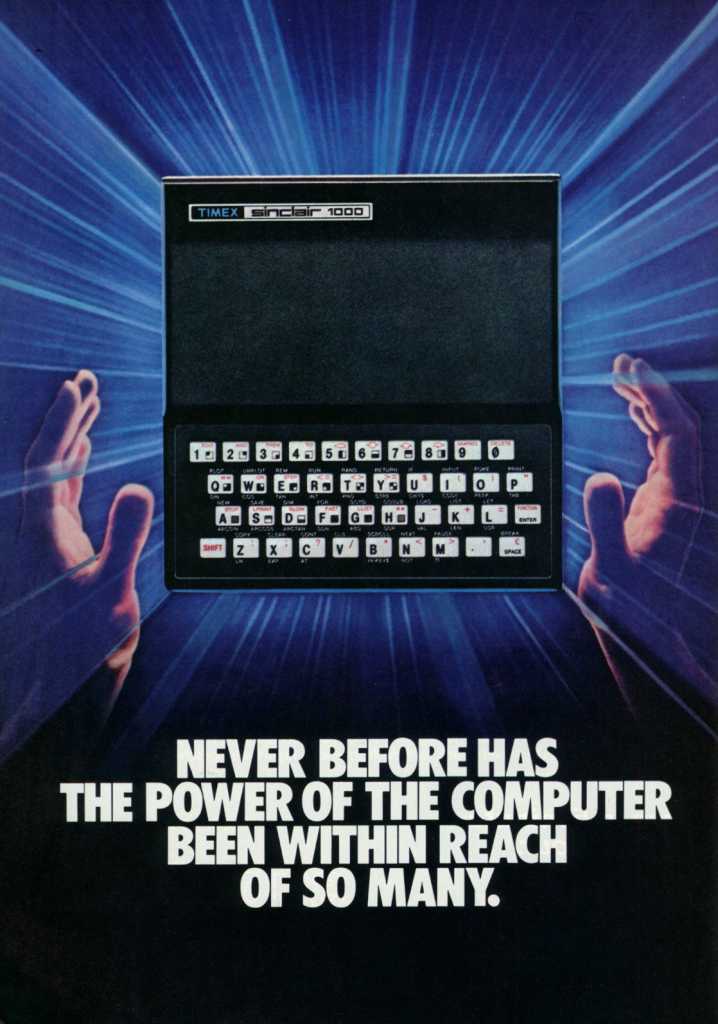

Timex/Sinclair-1000 ad from 1982 [click to enlarge].

The ZX81 sold millionfold and became so successful that it raised interest in the US. Timex distributed it there as the Timex/Sinclair-1000, which, apart from NTSC video output, was identical to the ZX81. Interestingly, T/S-1000 units with PAL output made in Portugal were later also distributed in Europe.

Characteristics

Well, what can you say about the ZX81? Two words sum it up: sheer agony! Its ergonomics were unspeakable and its performance utterly abysmal even in its day. But let's be objective with this little guy, shall we? :^)

For £70 you got a little black box barely larger than your hand

with a membrane keyboard, BASIC in ROM, 1K of RAM, a tape interface, and

rudimentary monochrome video via an RF modulator. To be fair, the ZX81 was

a real computer, albeit a severely limited one. In order to cut

costs, Sinclair stripped the ZX81 of all the non-essential features. What

you end up with is a system that is so extraordinarily limited that it's

all the more remarkable that people actually managed to achieve anything

with it at all. Among the stunning software I've seen for it is the 1K ZX Chess

(with crude text mode board

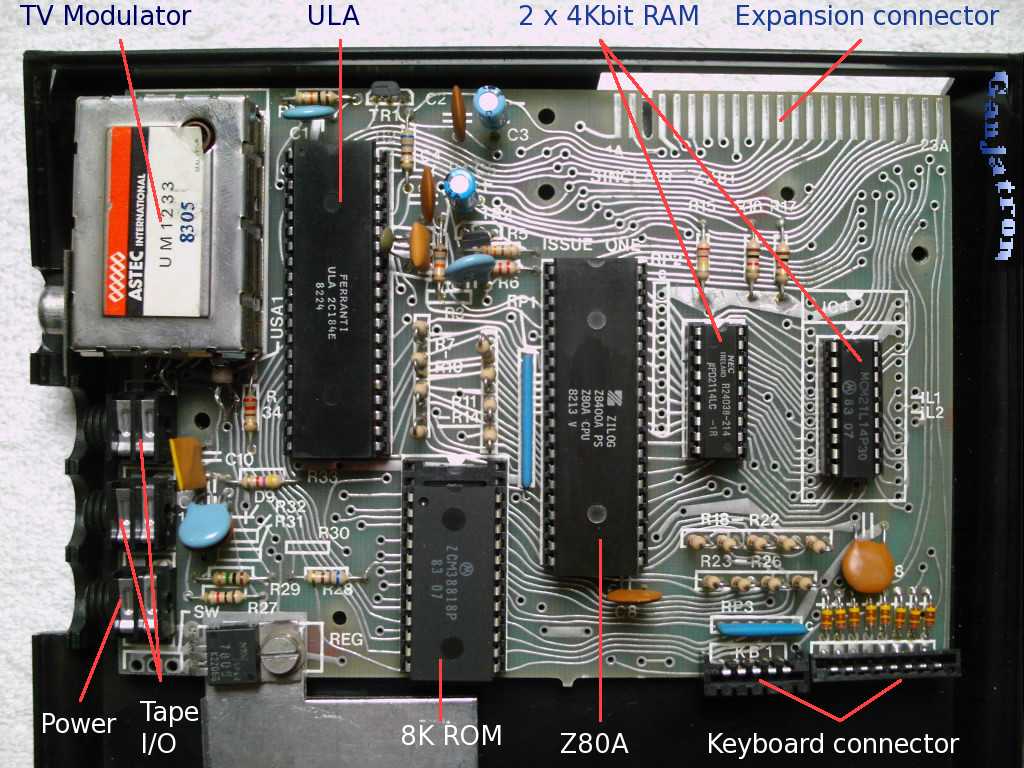

| The ZX81 motherboard. Yes, that's all there is -- just five chips! Most of the logic is stuffed into that Ferranti ULA. Note that there's an option for one 8Kbit (1Kbyte) RAM marked on the board around the right RAM chip. Later revisions used this for a total of just four chips instead of the two 4Kbit (512 byte) RAMs seen here. Remarkably, Sinclair provided each IC with a socket in spite of the overall low cost. [click to enlarge] |

Sinclair achieved the target selling price by skimping on the following components, in some cases severely impairing the system's usability:

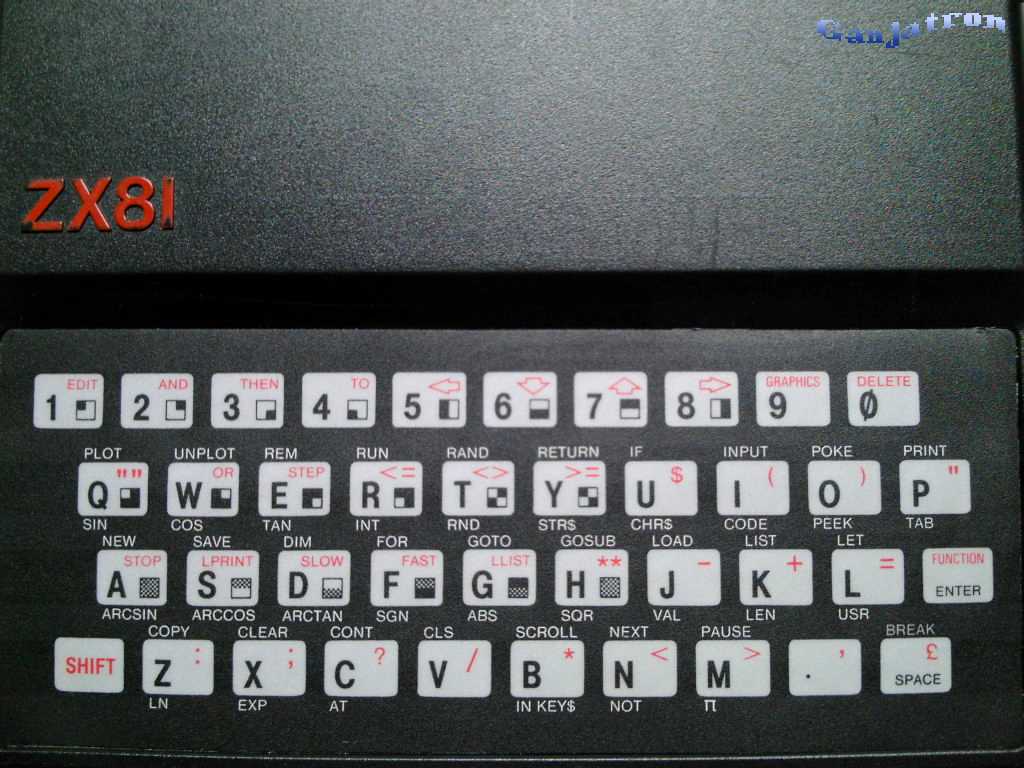

- Keyboard

- This is simply the ultimate abomination of the ZX81, and without doubt the worst "keyboard" ever fitted to a microcomputer. It consists of a totally flat membrane without any feel or feedback, and poor response. To make life a little easier, BASIC keywords can (and must) be entered with a single keystroke. That's no real consolation, on top of which it results in a confusing fivefold (!) key labelling scheme. As already mentioned, the keyboard connector is a fundamental design flaw, consisting of a fragile semitransparent foil with printed leads. This material becomes brittle with age and literally crumbles when handled, rendering many a ZX81 useless nowadays. Needless to say, many ZX81 users soldered on an external keyboard, even if the original still worked.

- Display

- A colour display was obviously out of the question, so the ZX81's output is entirely monochrome. Nevertheless, it still offers a graphics mode, albeit lo-res with a paltry 64×48 pixels (apparently there were also some cosmic programming tricks to obtain hi-res graphics at 256x192). The major cost cut manifests itself in the absence of a dedicated display processor: scanning out the video is taken care of by the Z80, leaving only the vertical blanking period to execute programs! This is the so-called slow mode, and believe me, it is pathetically slow. As an option, there's also a fast mode in which the Z80 executes programs full time while the screen goes spastic, flashing on every keystroke! Eventually the user also goes spastic during prolonged sessions.

- Memory

- Low cost inevitably meant low memory capacity; there really isn't a helluva lot you can accomplish with just 1K of RAM. The 16K RAM expansion pack was therefore almost a necessity, not just an add-on.

- Sound

- There is no built-in audio; the ZX81 is mute. Turning up the volume on the telly produces some pretty funky hum and buzz, tho. Programmers found that alternating sequences of slow and fast mode produced some particularly interesting sounds. :^)

- Power switch

- There's no power switch; you have to unplug the adaptor. Of course the UK, like all Commonwealth countries, has those cool switchable outlets, so they never missed it.

- Build quality and reliability

- The ugly, characteristic wedge-shaped case (disparagingly referred to as the "doorstop") consisted of flimsy black plastic. It bows and creaks when you apply pressure to particularly unresponsive keys. The expansion connector was of course not gold plated, and oxidised easily, yielding poor contact. As a result, jiggling the case with the 16K module plugged in usually resulted in a crash. Quality control was also substandard, particularly with T/S-1000 units; an estimated 30% left the factory as duds! Obviously, mine was among that number.

- Motherboard

- Sinclair shrunk the number of chips on the motherboard to just

five (four on later revisions which use one 8Kbit RAM instead of two

4Kbits), thereby saving costs by integrating several components into a custom logic array (specifically a Ferranti uncommitted logic array, or ULA). This chip the size of the Z80 CPU itself takes care of tape I/O, video signal generation, and keyboard scanning, among other things. Practically all manufacturers would later adopt large scale integration in custom chips as a cost and space saving measure. Surprisingly, Sinclair actually bothered to socket all the chips on the board, facilitating replacement (I've managed to fry the Z80 on one).

The ZX81 has a number of bizarre features, some of which were no doubt

dictated by the system's design constraints. The display, for instance,

doesn't scroll automatically, but pages instead; when the output reaches

the bottom of the screen, the ZX81 pauses and waits for a keystroke

(CONT, I

Another notable peculiarity is the entry method. All input is done at the bottom of the screen, be it program entry or prompted input. The last few lines of the screen were reserved for input, while the (at most) 22 lines above it were exclusively for output. The cursor will never appear in the output region.

A further oddity is that commands are parsed as they are being entered. This means the ZX81 prompts you for the type of tokens it expects by inverse characters appearing in the block cursor:

- "K" indicates an expected BASIC keyword (GOTO, GOSUB, etc)

- "L" indicates an expected literal (i.e. numeric constant or variable name)

- "F" indicates an expected function (SIN, COS, etc)

- "G" indicates an expected graphics character

This parsing on the fly constitutes one of the ZX81's most outstanding idiosyncrasies: syntax errors are caught immediately after you enter a program line, not when it is executed as with other BASIC interpreters. This is indicated by an inverse "S" at the exact token where parsing failed, which is surprisingly sophisticated for an El Cheapo compie.

| Mark my words: you haven't experienced hell until you've tried to type on this... [click to enlarge] |

As memory (inevitably) begins to run out on the ZX81, really weird stuff happens; the command parsing breaks down and syntax checking fails, your program only lists partially, and, when things get really dire, the cursor and even the line you're entering may disappear completely! This is because the ZX81's display isn't memory mapped, but rather stored in a dynamic display file in the form of variable-length text strings (!) which share their space with user variables. Apparently the display file is simply truncated if it no longer fits, leaving you in the dark.

Yet another spastic trait of the ZX81 is that fact that the tape interface's signal uses the same pin as the video sync coming from the Ferranti logic array, creating crazy zig-zagging jittery lines all over the screen. While a technical necessity, it also gives the bored user something to watch while waiting for the damn tape to load.

On a positive note, the Sinclair BASIC in ROM is surprisingly rich for a low cost computer, offering some commands which other simpler BASIC dialects of the time lacked. Its floating point precision (9.5 digits) was also above average for its day. Substrings are handled with a so-called slicing construct <string>(<start> TO <end>) instead of the more common LEFT$, MID$, and RIGHT$. Incidentally, the character set is not ASCII but entirely proprietary, including 22 graphics characters. A shortcoming of Sinclair BASIC is the lack of multistatement lines, which is particularly a nuisance with conditionals.

To sum up, the ZX81 was a fab introduction to personal computing, but sooner or later everyone screamed for more. I too had my share of agro with this thing, and have mixed feelings about it in retrospect. Don't get me wrong; given the constraints imposed by the original target price, this is one of the most interesting micros ever devised, and I acknowledge that Sinclair had a challenge on their hands which they tackled with great success. For its time and for its price it was a great beginners' computer, but it was simply too limited for any serious applications. From a modern perspective, it's a unique machine that fascinates in its simplicity and one can't help but admire programmers' efforts in pushing the hardware beyond its design limits.

Hardware Issues

- Deterioration of keyboard connector is a canonical flaw affecting all units, requiring replacement of entire keyboard membrane. Replacements available from RWAP Software.

Specs

| Year of introduction | 1981 |

|---|---|

| Retail price | £70 (ZX81 assembled) £50 (ZX81 kit) $100 (T/S-1000 assembled) |

| CPU | Zilog Z80 at 3.25 MHz |

| RAM | 1K (16K with RAM expansion pack) |

| ROM | 8K with Sinclair BASIC |

| Display | 64×48 monochrome graphics 32×24 monochrome text |

| Audio | None |

| I/O | Expansion connector, cassette in/out, RF modulator out |

| Storage | Audio cassette |

| Keyboard | Membrane keyboard with keyword entry, upper case only |

| Operating system | Proprietary |

| Rarity | Common |

| Verdict | Classic instrument of torture for the masses |

Links

The original ZX81 homepage (?)Matt's ZX81 homepage

ZX-Team homepage

Planet Sinclair (Sinclair stuff in general)

Matthias Jaap's ZX81 website (includes excellent software archive)

An homage to the ZX81 and T/S-1000 (Kraut, lots of hardware info)

Sinclair FTP archive (general Sinclair resource including emulators and software)

Replacement keyboard membranes from RWAP Software

Back to Retrocomputing

Back to GanjaTron's Site

Back to GanjaTron's Site