Back to GanjaTron's site

Back to GanjaTron's siteRolleiflex TLR

Rolleiflex 2.8C with Schneider Xenotar lens, ca. 1953 vintage [click to enlarge].

The Rolleiflex TLR (Twin Lens Reflex) is a true classic of photographica. It defined a whole new species of camera and set new standards in quality, becoming the instrument of choice for a whole generation of fashion photographers and artists. Its lens captured celebrities and movie stars on film and immortalised them in classic glamour shots which have become popular iconographs today. It was the backbone of the Rollei product line for decades and became synonymous with the company name. Even today, Rollei still maintains its TLR tradition in the form of the modernised 2.8 FX.

History

The original TLR design was the brainchild of Reinhold Heidecke, head tinkerer and co-founder of Franke & Heidecke in Brunswick, Germany (now known as Rollei Fototechnic). The idea was to develop a mirror reflex camera in as compact a package as possible, using the (then relatively new) medium format rollfilm. At the same time, parallax should be minimised.

Heidecke developed a number of prototypes from 1926 to 1928 before the camera went into production in early 1929. The shutter technology of the day precluded the implementation of a reliable mechanism for a swinging mirror as used in modern SLRs, particularly in medium format. Instead, a fixed mirror was used with its own dedicated lens for the viewfinder. The fixed mirror meant no mechanical wear and tear, and is the key to the Rolleiflex's longevity.

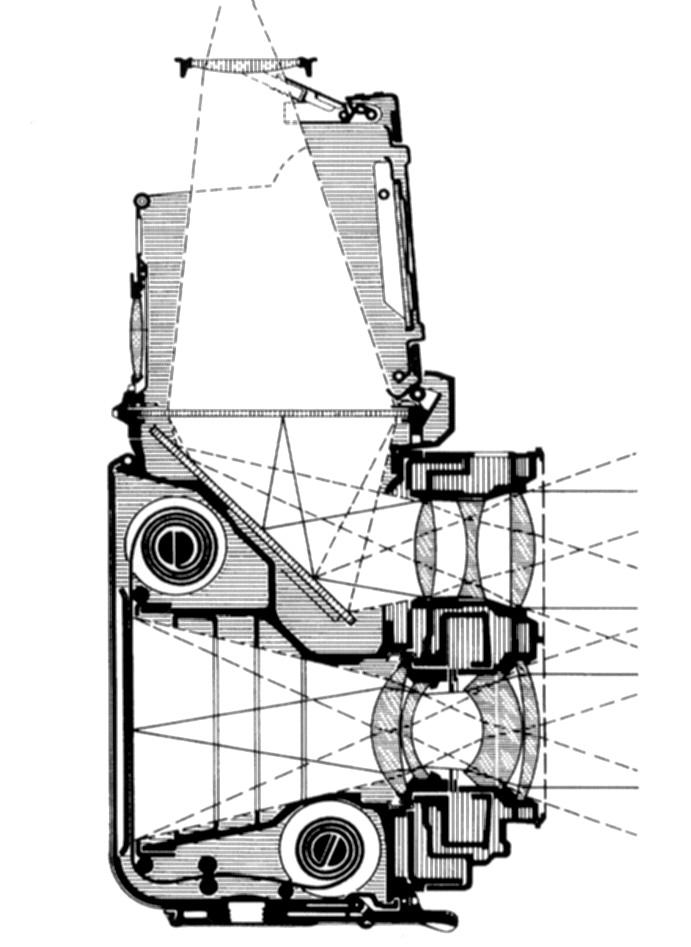

Heidecke also realised that the separate finder and taking lens must be mounted as close as possible to minimise parallax. At the same time, however, the payout and takeup films spools needed accommodation in this cramped space. He solved this problem brilliantly by placing the payout spool just below the taking lens (outside its field of view), and the takeup spool in the empty nook behind the mirror. A waistlevel finder with groundglass and hood topped off the handy package. Rollei religiously patented everything they designed, and the competition was forced to go other -- often bizarre -- ways. Consequently, some manufacturers simply slapped the film spool recesses as protrusions onto the back or sides of their cameras, making them bulky and just downright ugly.

Cutaway schematic [Click to enlarge].

The viewing and taking lens were fixed and not changeable, an ephemeral point of critique which the competition were quick to point out and which ultimately led to the demise of the TLR and the arrival of the medium format SLR. Rollei never revised its philosophy of fixed lens on its TLRs based on a simple but overly important criterion: imaging quality. The key to the Rollei TLR's quality were the extremely low manufacturing tolerances. Interchangeable lens cannot meet these specifications, and the idea never materialised in production models, although I believe some prototypes were built.

The Rolleiflex was always a pricey camera, but it was an immediate success. Its precision design and manufacture resulted in a camera whose build and image quality was (and still is) superb. Many imitations emerged over the decades since its introduction, but none equalled it. Yashica and Mamiya are perhaps the best known competitors and offered TLRs in a lower price segment with considerable success. Mamiya in particular addressed the Rollei's primary "deficiency" and offered models with interchangeable lens.

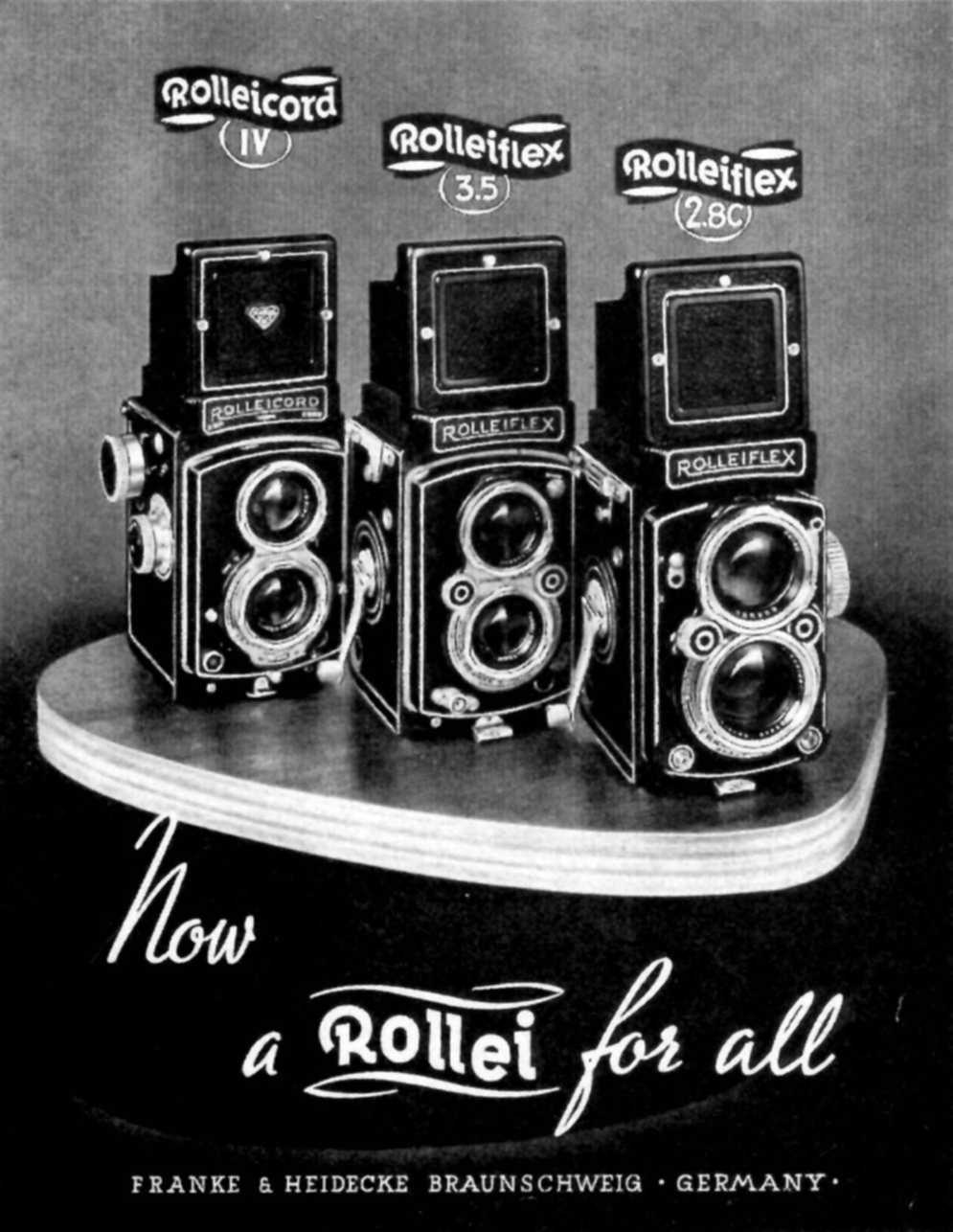

Rollei realised early on that they had to react to the mounting competition by introducing an economy model: the Rolleicord. The Cord differed from the Flex in a number of ways. Among the simplifications made were the replacement of the trademark film advance lever by a simple knob, and a simpler shutter which had to be manually cocked by a lever.

Rolleiflex/Rolleicord ads [Click to enlarge].

The Rolleiflex had its heyday in the 50s and 60s, during which it became the camera of choice for any self-respecting photographer and photojournalist: Milton H. Greene, Philippe Halsman, Richard Avedon, Bert Stern, Cecil Beaton, and Weegee, just to name a few. The Paparazzo character in Fellini's "Dolce Vita" totes a Rolleiflex throughout the movie, typifying a new breed of aggressive photographer at the time. By the late 60's medium format SLRs began to take over. Along with Hasselblad, Rollei itself entered this market, and interest in TLRs began to fade. But the TLR isn't dead: even today, Rollei still maintains its former niche with small production numbers of modernised TLRs, complete with electronic TTL metering. However, some die-hard aficionado pros still swear by the old fully mechanical workhorses and prefer them to their modern electronic descendants.

Characteristics

The TLR camera body is machined from a single aluminium block lending it great stability. Real leather covers the majority of the outer surfaces. There are hardly any plastic parts on the body (although rising production costs gradually increased the plastic/metal ratio over the decades). Overall, the build quality is impeccable. The weakest part of the design is the soft aluminium lens hood and back of the camera, which are subject to deformation in the hands of morons.

Machining the camera body [Click to enlarge].

(From Rollei-Report #2 courtesy of the author)

The viewing and taking lens are mounted on a common lens board which ensures they remain in the same plane. The lens board moves in and out supported by guides in the camera body. The lens and film planes must be exactly parallel in order to ensure optimal imaging (Rollei developed its own specialised tools for this alignment). The lens board is the Achilles' heel of the Rolleiflex: if it receives a heavy blow it may need realigning, which can be a costly affair (provided you find someone who can do the job).

The lens vary from model to model, generally falling into the f/3.5 and f/2.8 categories. Typical for the Rolleiflex 3.5 line are the Zeiss Tessar (later also Planar), or Schneider Xenar. The Rolleiflex 2.8 has a more prominent "bug-eyed" lensboard to accommodate the larger lens and usually comes with Zeiss Planar or Schneider Xenotar lens. There have been endless religious discussions between adherents of the Zeiss and Schneider camps over which is the better lens. In practice, they perform equally well: people who actually use these cameras have made numerous comparisons and concluded that the differences are minimal. However, collectors almost always insist on Zeiss lens (everybody knows the name), and are willing to pay substantially more over a cheaper Xenotar, even though the performance is virtually identical.

The prominent film advance lever gives the Rolleiflex the amusing appearance of a miniature movie camera. Infact, it's only fully wound when loading film. After an exposure, the lever will only go about 1/3 turn, and is returned to its home position. This mechanism is foolproof: Once the film has been advanced, the lever is locked in place until the next exposure is made.

The shutter is a leaf type coupled with the film advance lever. A self timer can be found in the upper left or right corner of the lensboard. The shutters are remarkably quiet (particularly on the f/3.5 models) and give the camera a subtle, unobtrusive quality. Post-war Rolleis had shutter speeds ranging from 1--1/500 sec originally in non-linear progression before adopting modern linear shutter speeds in the mid 50s.

The two prominent thumbwheels between the taking and viewing lens set the basic exposure parameters: time and aperture. Later models also featured the EV (exposure value) system used on many light meters, enabling the photographer to mechanically couple the two thumbwheels and change parameters while maintaining the same exposure.

Later Rolleiflexes were fitted with a coupled Selenium light meter (also available as an option). The meter was built into the focus knob while the Selenium cell was incorporated into the nameplate, requiring the Rolleiflex logo to be reduced. Personally I find this unsightly, and opted for earlier models without this feature. I also figure an external light meter is more accurate and easier to repair or exchange. (My classic Gossen Lunasix does the job nicely).

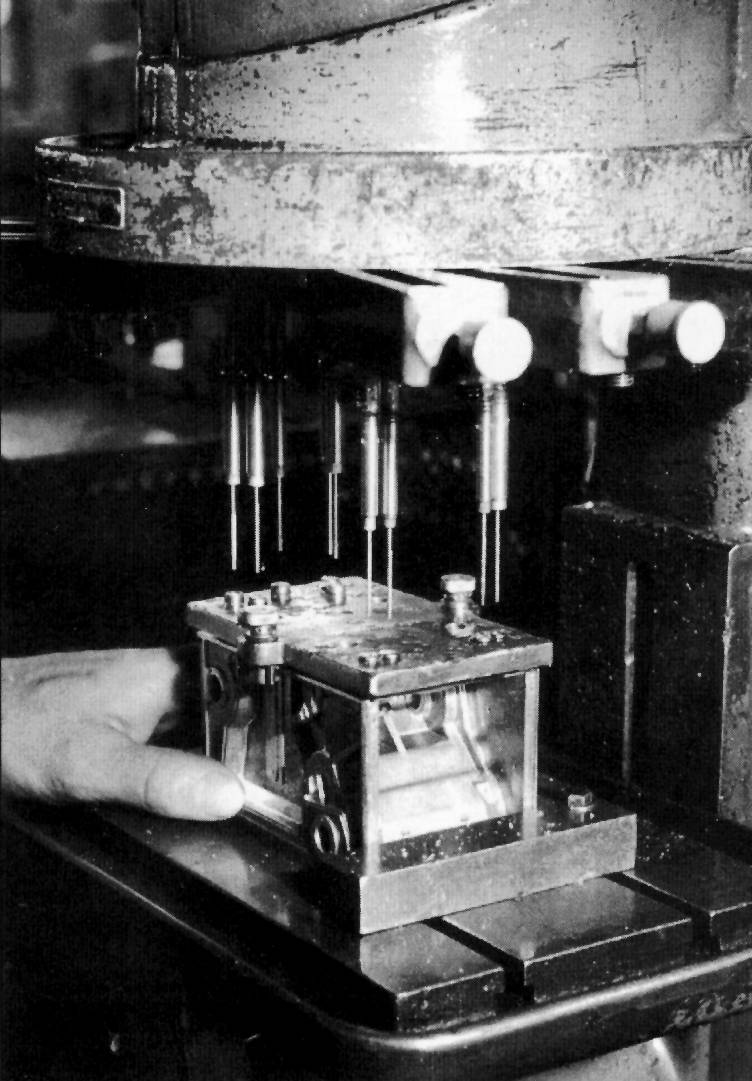

All postwar Rolleiflexes are "automats", i.e. they sense the first frame on the film. This feature uses a patented mechanism developed by Rollei which actually distinguishes between the combined thickness of the film and backing paper, and that of the backing paper alone. A special tool was used to fine tune this sensor in the factory. By contrast, the Rolleicord requires the film to be manually advanced until a marking on the backing paper shows (which is still the modus operandi when loading magazines for professional TLRs even today).

Factory adjustment of feeler mechanism [Click to enlarge].

(From Rollei-Report #2 courtesy of the author)

Handling

The Rolleiflex TLR takes some getting used to. The waistlevel finder is irritating at first because everything is reversed! Holding and operating the camera is also awkward for novices. The general idea is to cradle it in your hands and trip the shutter with your right thumb or index finger, with your left hand on the focus knob. For those new to medium format, film loading can also be a challenge.

The TLRs typically weigh in at 1 Kg (subject mainly to the type and weight of the lens) and can become quite a burden if lugged around for extended periods. It's downright uncomfy to have one dangling from your neck. Still, it's actually lighter and smaller than most medium format SLRs.

Given the camera's bulk and expense (in terms of purchase, maintenance, and film), it is not the kind of camera you take around just for fun or casual snaps. It requires a more deliberate approach. I only lug it when I know for sure I'll encounter something worthy of a precious medium format exposure (remember each roll has only 12 shots). If you're a hobbyist, this is a camera for special occasions. Of course, if you're a pro you'd be using it every day...

At the end of the day, however, the TLR's idiosyncrasies and awkwardness pay off with spectacular exposures. Medium format transparencies are a special treat. Their brilliance and sheer sharpness conveys a tangibility and texture I've never seen in 35mm photography (of course, I haven't had any experience with Leica, but that's another story). The advantages of medium format also come to bear when dramatically enlarging negatives with little degradation in quality.

Of course, wandering around with a TLR nowadays will inevitably trigger strange looks from pimply faced digicam geeks. Do I care? :^)

Pros

Cons

Links

Claus Prochnow's excellent Rollei-Report book seriesA Pictorial History of the Rollei 6x6 Twin Reflex

Ferdi Stutterheim's Rolleigraphy

Rollei TLR 6x6 Cameras -- User Review

The Classic Camera: Rolleiflex

Rolleiflex Manuals [archived]

Torbjorn Aase's Rolleiflex TLR page [archived]

Camerapedia entry

Guide to Classic Cameras: Rollei TLRs

Back to photo stuff

Back to GanjaTron's site

Back to GanjaTron's site